NEW YORK'S ONLY FORMERLY-INCARCERATED LAWMAKER SAYS THREATS FORCED HIM TO GIVE UP SPOT ON ASSEMBLY CORRECTIONS COMMITTEE

EDDIE GIBBS SAYS HE'S 'TARGETED FOR RETALIATION' BECAUSE OF HIS ATTEMPTS TO REFORM STATE PRISON SYSTEM AFTER ROBERT BROOKS MURDER

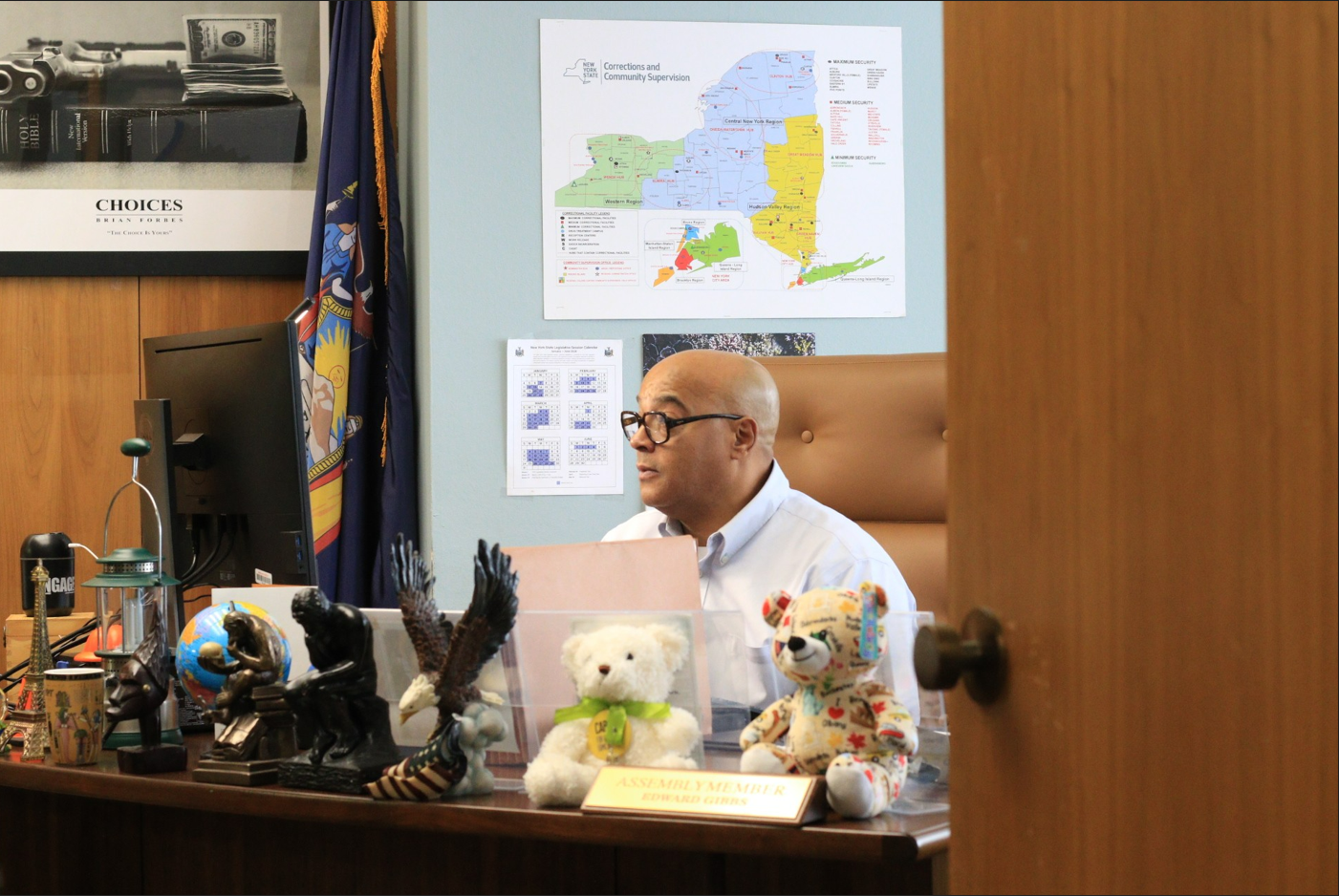

New York Assembly Member Edward “Eddie” Gibbs in his office at the State Capital in Albany, Feb. 3, 2026. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

EXCLUSIVE Feb. 4, 2026

Eddie Gibbs, New York's first and only formerly-incarcerated lawmaker, called this reporter crying on Tuesday.

"Jay," he said, "I need you to come to my press conference at the Capital tomorrow."

"I'm at my wit's end," he explained. "I'm just gonna step down from the committee and take a step back."

As much as I've seen and experienced in 55 years as a New Yorker and 20 years as a full-time journalist, I've never been called by a politician crying. He spilled his guts for 15 minutes. He told me the political class in Albany had turned against him since his election to represent New York's 68th District in 2022. Gibb's district covers his home turf of Spanish Harlem, the Upper East Side and the islands in the East River.

The committee he planned to resign from was the State Assembly's Committee on Corrections—a plum assignment he's held since his election. Gibbs explained, through tears, that his tipping point came when Eric “Ari” Brown, a Republican colleague in the Assembly, cursed at him on the Assembly floor, poked him in the nose with his finger and invited him to fight on the street outside the Capital.

Brown, Gibbs said, took exception to what Gibbs described as a polite request that Brown not use the word "inmate" to describe what state law requires state officials to call "incarcerated individuals." Brown used the word 17 times, Gibbs said, during a debate on proposed prison reform legislation following the murder of Robert Brooks by guards at New York's Marcy Correctional Facility on Dec. 9, 2024.

To Gibbs, and a lot of other formerly-incarcerated individuals, "inmate" is an insult.

"Fuck you. Fuck you motherfucker," Gibbs said Brown yelled at him, on the State Assembly floor.

"I just sat there and took it," Gibbs recalled. "If it had been me I would've been arrested. Thrown out of the Assembly."

Gibbs said he asked Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie to discipline Brown, but so far nothing has been done. As a result, he hasn't returned to the Assembly chamber. He works from his office, on the seventh floor of the Legislative Office Building across the street from the Capitol.

"I can't go back in the Chamber when they didn't do anything to him," Gibbs said. "The guy threatened me. No sanction, no recourse, no nothing."

New York Assembly Member Edward “Eddie” Gibbs in his office at the State Capital in Albany, Feb. 3, 2026. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Gibbs is one of two or at most a handful of lawmakers with felony criminal records in America depending on whether you count people who are not open about their prison pasts.

When Gibbs called, I wasn't sure at first whether he was calling me as a journalist or whether he was calling me because I'd done time in New York for manslaughter too and he wanted to commiserate with someone who knew the unique challenges we face. Instead of immediately publishing what would have been a tasty and exclusive news scoop, I tread lightly and listened.

I also decided to take Gibbs up on his invitation to go to the State Capital in Albany on Wednesday when he would publicly announce his decision to quit the Corrections Committee in a news conference. Until then, the news would have to wait.

Gibbs' ascension to the State Assembly was heralded by a glowing profile in the Village Voice and, when he managed to win re-election in 2024, the New York Times. But since then he's committed a handful of what tennis players might call "unforced errors" in the cutthroat world of hardball New York politics.

First there was his October 2024 detention by the NYPD for strenuously objecting to his brother's arrest. (The New York Post reported Gibbs was arrested for disorderly conduct, but Gibbs says he wasn't even given a ticket.)

Then there was an election brouhaha over allegedly misleading mailers. It ended with 17-term Jewish Congressman Jerry Nadler calling Gibbs an "anti-semite"—a vague and vogue charge de jure Establishment politicians have been making against a lot of status quo-shaking upstarts lately. For example, Zohran Mamdani.

Gibbs' latest controversy started during a vote on a resolution to mourn the death of beloved Harlem congressman Charlie Rangel, founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus and—before his death—lone survivor of the legendary “Gang of Four.”

“My mother was a big fan of Adam Clayton Powell, the congress member. And she would tell me often that Adam Powell made her moist,” Gibbs said in a floor speech.

“And then when Charlie won the seat—had the seat, she said Charlie made her wetter,” Gibbs said.

The Assembly Ethics Committee found Gibbs violated policy by making "sexually explicit remarks on the Assembly floor." It recommended "a written warning to Member Gibbs and require that Member Gibbs undergo counseling to address the use of sexually explicit remarks and the use of professional communication."

Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie accepted the Committee's recommendations.

To Gibbs, the Assembly's failure to investigate Brown for blowing up at him inside the Assembly chamber, after the Assembly sanctioned him for merely speaking banned words, suggests a double-standard.

Neither Brown nor Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie responded to requests for comment.

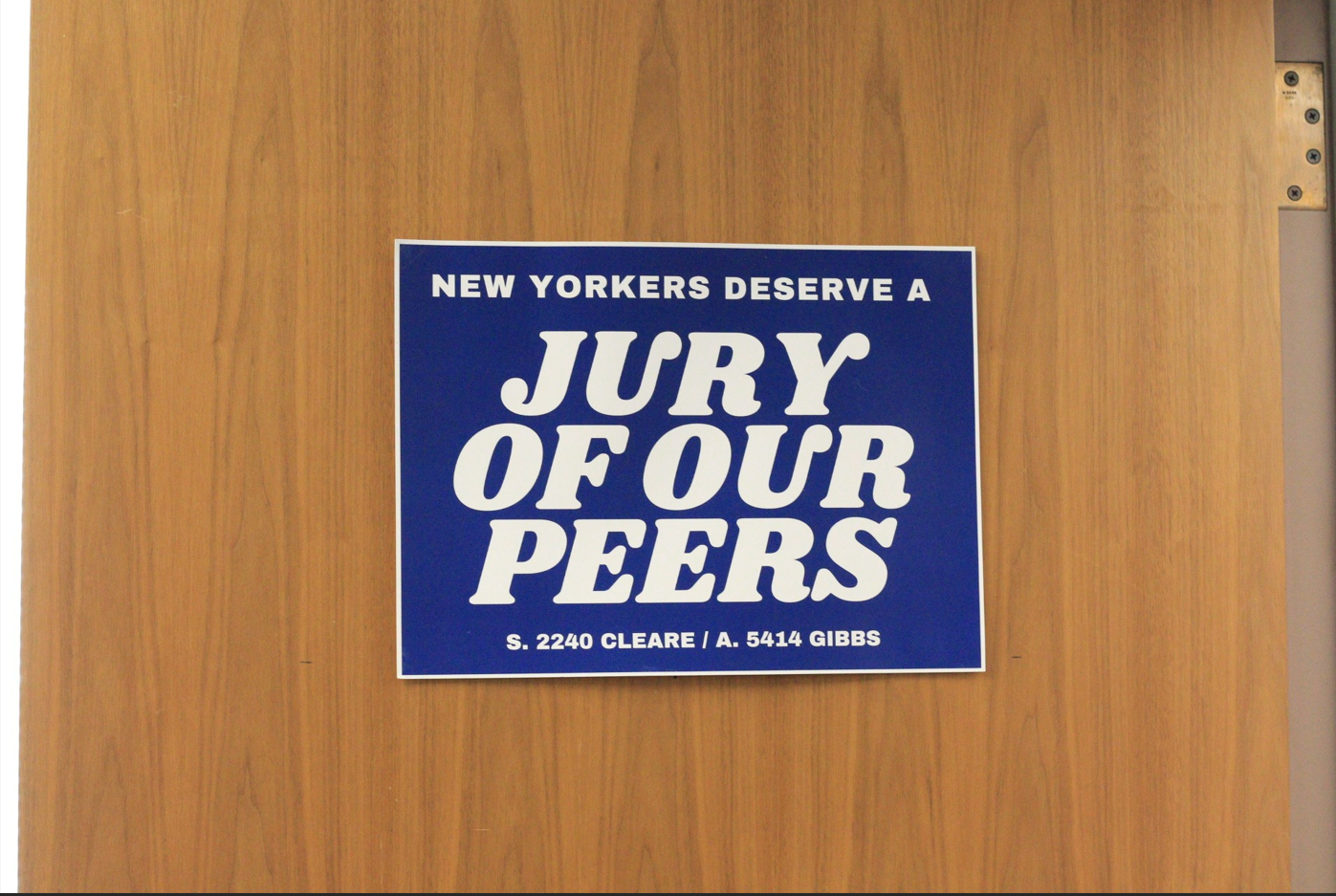

A poster hanging in the office of New York Assembly Member Edward “Eddie” Gibbs at the State Capital in Albany, Feb. 3, 2026. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Gibbs scheduled the news conference where he would publicly announce his resignation from the committee for 1:00PM. I went straight to Gibbs' office when I got to the State Capital around 11:30AM. Now 57, Gibbs says he didn't decide to become a politician until late in life.

"It wasn't in my periscope," Gibbs told me.

He credits a Jewish mob lawyer from the Bronx with inspiring him. Murray "Don't Worry Murray" Richman is a Bronx legend. He started out representing small-time crooks before becoming famous for defending Gambinos and Genoveses, as well as DMX and Jay-Z.

"Murray talked me into it," Gibbs said. "I went from breaking the law, to making the law."

(Full disclosure: Murray represented one of the three men who got immunity to testify against me. Their testimony got me sent to prison from 1990 until 2003.)

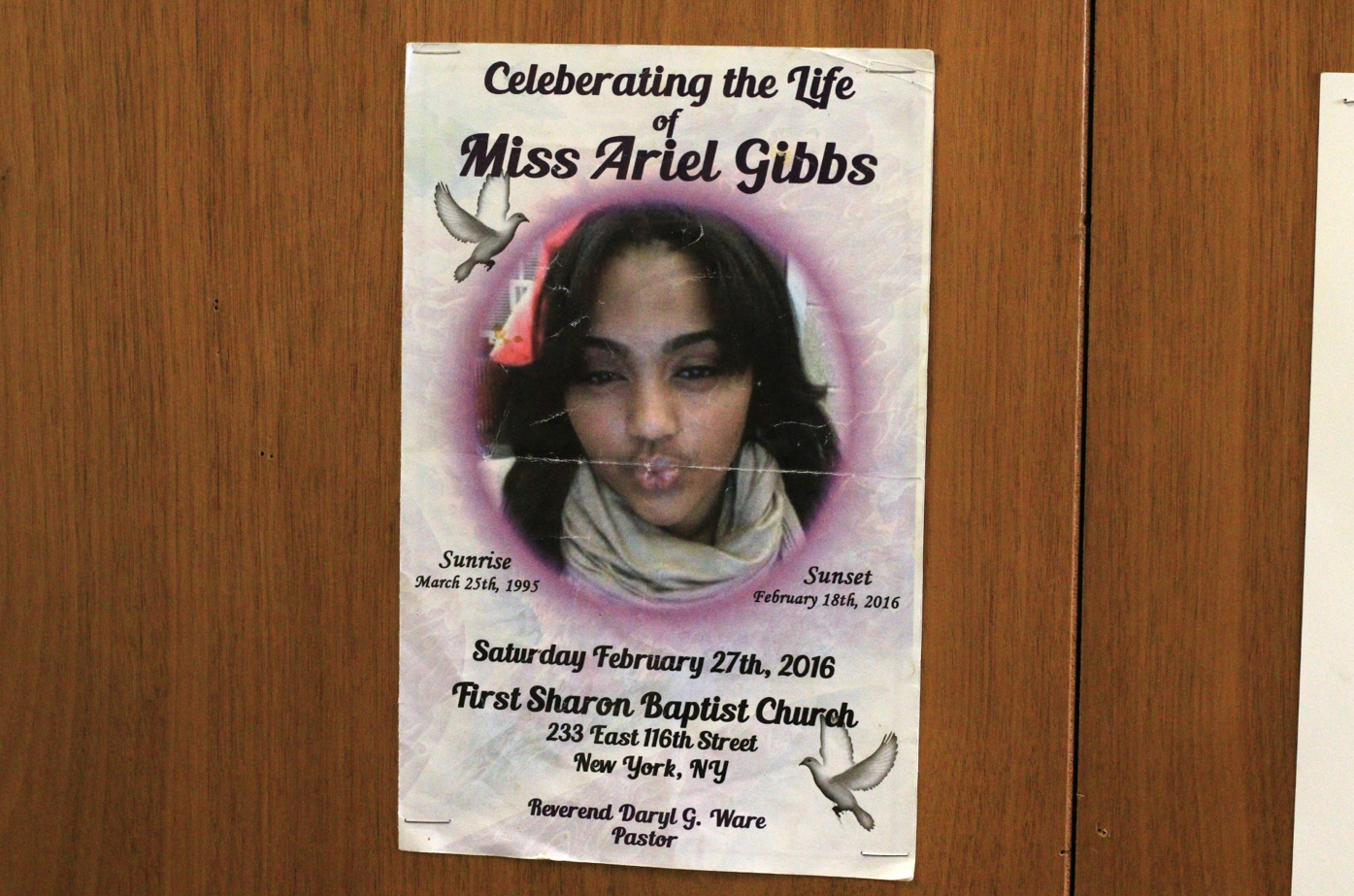

Gibbs' daughter, Ariel, died a month short of her 21st birthday in 2016. He keeps a memorial to her on his office wall. Since then, he's raised her two children, Ian and Myrian, now 11 and 12 respectively. He keeps photographs of his grandchildren on his desk.

All around his office are reminders of his past. If you're not supposed to forget where you came from, this is how Gibbs does it.

On the wall next to his desk is a map of New York showing the locations of its 42 prisons. Next to it is a poster-sized photograph by Brian Forbes depicting a gun and a wad of $100 bills resting on top of a bible. I asked Gibbs what it meant to him.

"Brian Forbes, in that picture," Gibbs answered, "is saying pretty much you have a choice. You can go for the money, you can go for the gun or you can go for the bible. The choice is yours. Nowadays I would go for the bible."

Then there's the pair of "state greens" hanging in his office closet.

In New York, a state prisoner's two-piece shirt and pants prison uniform is colored forest green. When they're washed 100s of times, they fade. The state greens hanging in Gibbs' office were faded. The short-sleeve shirt bore a white patch with his name and unique, alpha-numeric identification code printed on it. Gibbs' number was 88-B-2173.

"I will never forget those numbers for the rest of my life," Gibbs told me.

(He's right. My own was 91-A-6991.)

We sat down to talk. He handed me a copy of the resignation letter he sent to Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie.

"It has not been easy serving as the first formerly incarcerated individual in the history of this state," the letter read. "Much is expected, but you also become a lightning rod, a target for attacks by those who seek to undermine both me personally and the larger movement for the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated."

Memorial to Gibbs’ daughter that hangs in his State Capital office. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Gibbs says his real problems started after Brooks' murder by an all-white gang of guards at New York's Marcy Correctional Facility outside Utica. The gang tortured, beat and choked Brooks to death in a caught-on-camera killing that shocked and sickened the Nation.

Gibbs circulated a petition addressed to Gov. Kathy Hochul calling on her "to immediately close Marcy Correctional Facility." The petition, dated Jan. 13, 2025, garnered the signatures of 46 Assemblymembers and 17 State Senators. Gov. Hochul ignored it. After that, Gibbs said, his previously warm relationship with Gov. Hochul cooled.

State lawmakers have the legal power to visit correctional facilities. Before Brooks' murder, Gibbs said he visited many if not most of the state's prisons without facing static from prison workers.

"We had a real great working relationship," he said.

But when he visited some of the same prisons after Brooks' killing, it was different.

He points to body camera video obtained by the union that represents New York's prison guards from the state agency that runs the prisons, the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, or DOCCS. DOCCS routinely takes years to deny Freedom of Information Law requests from journalists, but in this case apparently granted the union's request for the body-camera video in less than a month. (Likely with Gov. Hochul's blessing.)

The video makes even Gibbs' supporters cringe. It captures Gibbs in an unflattering light, initiating a heated exchange with a sergeant inside Marcy when he visited and spent the night on Jan. 21, 2025—a month-and-a-half after Brooks' brutal murder.

Gibbs told me he confronted the sergeant with purpose. He did it, he said, because he'd been told she directed and participated in the unjustified and excessive beatings of prisoners and had never been charged with a crime or even disciplined by DOCCS.

The union, the New York State Correctional Officers & Police Benevolent Association, issued a statement condemning Gibbs because he "disrespected a female sergeant."

"His actions," Summers added, "are indicative of the disrespect and lack of support our members feel from our elected officials.

After the blow-up, Gibbs says he feared he was "targeted for retaliation." Whenever he visited prisons after that, when he came back outside he found his tires slashed, he says.

He also says people threatened his life on the Internet.

"Seems like right after they killed Robert Brooks and I took a stance," Gibbs told me. "DOCCS began threatening and attacking me because of that stance on Robert Brooks and ultimately Messiah Nantwi."

Nantwi was another New York state prisoner killed by guards. The 22-year-old was killed Mar. 1, 2025 at the Mid-State Correctional Facility, which is directly across the road from Marcy. Gibbs told me he had served part of his sentence at Mid-State. It was, in fact, the prison he was paroled from in 1992. Nantwi’s killers were charged and their trials scheduled for Spring.

Because of the threats, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie budgeted funds to hire someone to accompany Gibbs on prison visits.

"Carl has been very supportive," Gibbs told me. "To make sure I was safe in prison he hired Nate Lucas."

Lucas was in Gibbs' office when I visited. He's a Harlem Jazz musician but he looks—at least to me—like a character straight out of Colson Whitehead's 2023 Harlem novel, Crook Manifesto.

Even with Lucas, "It's just unsafe for me to be in correctional facilities anymore," Gibbs told me. "I don't feel safe."

DOCCS spokesperson, Thomas Mailey, told The Free Lance News that:

“These allegations were never reported to DOCCS for investigation. The Department will not tolerate misconduct by incarcerated or employees. After an investigation, if anyone is found to have committed a crime, they will be held accountable and where appropriate referred for potential prosecution. That said, these allegations were never reported to DOCCS.”

Gibbs holding the uniform he wore in prison, in his office at the State Capital in Albany, Feb. 3, 2026. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Before we headed to his 1:00PM news conference, Gibbs called DOCCS' Commissioner, Daniel Martuscello, on his mobile phone.

Gibbs wanted to give Martuscello a heads-up that he was quitting the Corrections Committee that oversees Martuscello's agency. Martuscello picked up on the fourth ring.

"Sir, how are you?," the prison chief asked the convicted killer-turned-lawmaker.

"My press conference is at one o'clock," Gibbs said. "I just want to give you a heads up."

"I'm taking a break," Gibbs explained. "This brother's in love and I don't want to fight no more. And I don't want my life threatened any more."

"I just want to be left alone," Gibbs rambled on. "And I want to be in love with the woman I'm in love with. She deserves better. I come home with anger issues and shit. She deserves more."

The Commissioner stayed silent and listened. When Gibbs finally paused, he spoke.

"You have a lot of talent," Martuscello said. "And after this last year we all had trauma."

"To the extent it's affecting you personally, or your life or your significant other," he added, "you gotta look at things for yourself first. You gotta make sure you're well and then your family's well and you can't do the work if that's not the case."

Gibbs agreed. He admitted he started "rationalizing 'Well, fuck that, my kids ain't in prison, my grand kids ain't in prison, fuck that, why I'm goin' crazy for.’ It's time to take a break. I need this mental relaxation."

Martuscello jumped back in.

"Listen man, it's OK to take a step back and say 'I need a break,'" he said. "We went through a lot of trauma man, we went through a lot of trauma together, and then couple that with the trauma you had from when you were incarcerated, right?"

"It takes a toll," Martuscello reflected. "People don't recognize that. People don't have the same life experiences that you had. And they don't have the same ones that I had."

Martuscello closed by telling Gibbs he would always pick up the phone when the lawmaker called.

"Keep in touch," the Commissioner said. "Don't be a stranger. Seriously."

"I appreciate you commissioner," Gibbs replied. "And I appreciate your friendship."

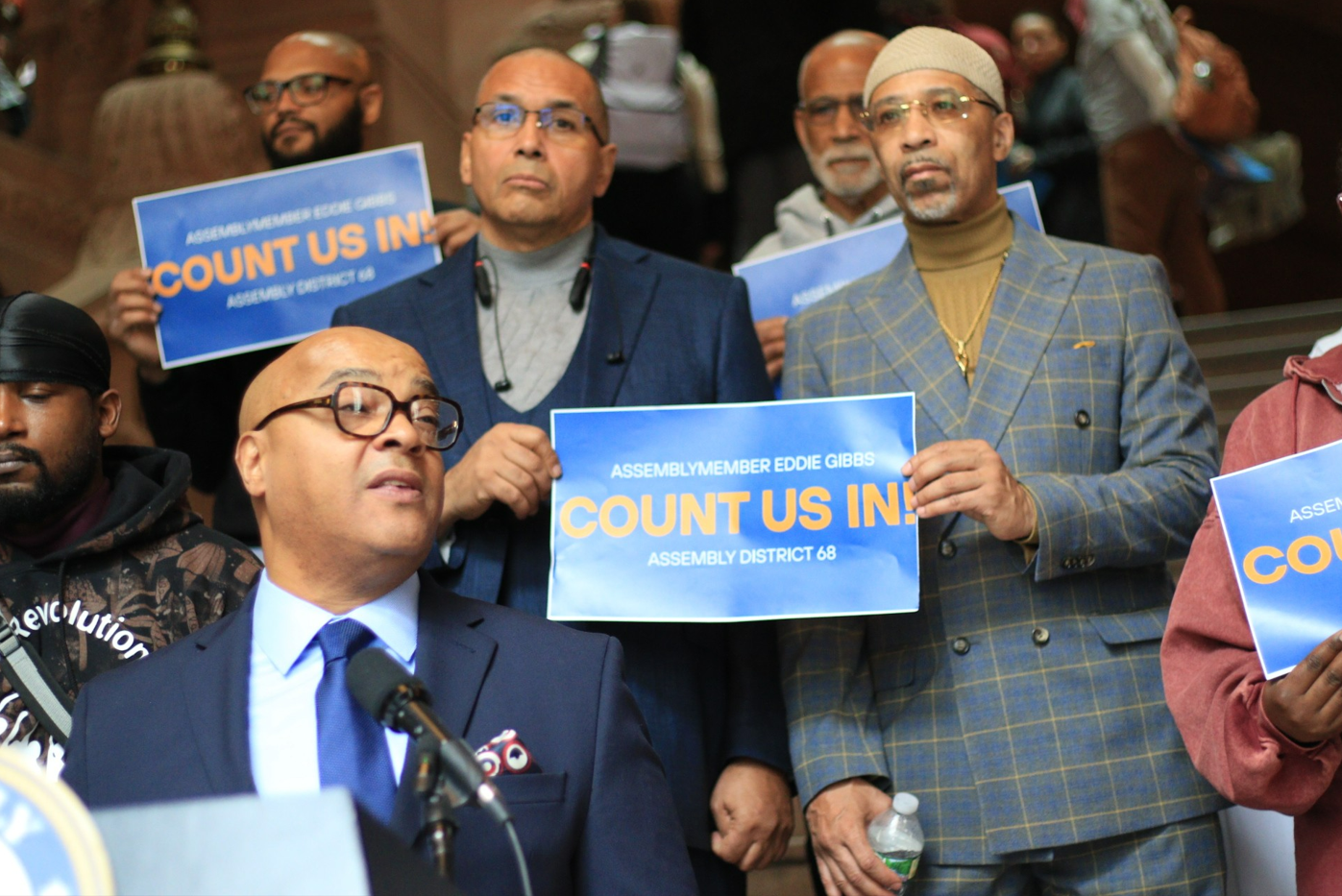

Gibbs holding a news conference on the Capital’s Million Dollar steps to announce his resignation and the formation of a new prison reform coalition, “Count Us In.” Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

As we walked through the office building's long hallways on our way to the Capital itself, where Gibbs' 1:00PM news conference was scheduled, Gibbs paused to say hello to several workers.

Fellow law makers recognized him, I saw, but Gibbs reserved his heartiest greetings for the support staff that make Albany work. This includes police. He spent several minutes kibitzing with State Troopers manning the secure entrance to the Capital.

Gibbs describes his man-of-the-people persona as a natural outgrowth of his East Harlem upbringing

"I'm a People-tician," he told me. "Not a Poli-tician."

Mike Lesser, a former New York State parole officer thoroughly experienced in detecting both bullshit and fronting motherfuckers, is one of Gibbs' neighbors in East Harlem. He saw this side of Gibbs up-close at a town hall-style meeting Gibbs held for constituents and thought it genuine.

"I thought he had a black belt in gently dealing with people that were 'affected,'" Lesser told me.

Lesser gave an example of "One person was complaining about how the street lights come on too early and wasting energy." He added, "my mom was a social worker for 44 years and he took care of this person with the exact same grace that she would have."

"It absolutely warmed my heart," Lesser added.

Gibbs' press conference almost lacked the press. Only one other reporter, from WAMC, was there beside The Free Lance News. Apparently, news an Assembly member was resigning from the Corrections Committee, because of tire-slashing and death threats by the prison guards he was charged with overseeing, wasn't newsworthy.

Notwithstanding the lack of mainstream journalists, several formerly-incarcerated men turned prison reform activists had Gibbs' back. They stood on the steps of the Capital's Million Dollar Staircase with him and denounced the system they were fighting against.

Thomas Kearney, co-founder of Capital Area Relief & Liberation, said what happened to Gibbs was "indicative of the culture of the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision."

Lukee Forbes, director of We Are Revolutionary, said "we are ourselves are really, deeply alarmed ... that [Gibbs] is being targeted while visiting correctional facilities, while being targeted for speaking up."

Garrett Smith, Statewide Organizer for the Center for Community Alternatives, said "it's a shame that he's going through this for justice, the pursuit of justice, we see the travesties that you're facing."

Anthony Dixon, founder of Parole Prep, which prepares prisoners for parole hearings and release, started out by observing Gibbs' resignation was taking place on the second day of Black History Month.

"Some people," Dixon added, "do not like the fact that a formerly incarcerated person got this assignment—and they can't do nothing about it."

Before Gibbs and his supporters left the news conference, they shook hands and hugged on the staircase. They pledged to fight together in a new coalition called "Count Us In."

Before returning to Gibbs' office, we got lunch in a public concourse beneath the State Capital. A handful of homeless people rested at tables in the dining hall. Gibbs went over to talk to one of them and offer him lunch. The man knew Gibbs, thanked him, but declined.

Back upstairs, Gibbs pointed to eight framed bills that hang on one of the walls of his office. The bills were sponsored by Gibbs, and made law. They included two bills that ensured students with disabilities have access to higher education by requiring textbook manufactures produce versions accessible to them, such as an e-textbook that works with a screen reader.

Two more authorized the Department of Environmental Conservation to regulate fishing for weakfish and bluefish—a seemingly odd subject for an urban lawmaker, unless you know a public walkway along the East River in Gibbs' district is a popular saltwater fishing spot where weakfish and bluefish are regularly caught.

Three of the bills dealt with issues unique to his district. One allowed a private nursing home to obtain public loans for renovations; one established the first cultural district in New York State: the East Harlem “El Barrio” Cultural District; and the third allows stickball organizations to get state funding to organize and advertise large stickball events likely to bring tourists to New York.

Two of the bills dealt with prisons. One required correctional facilities to tell parolees at the time of their release that they could vote. The other directs DOCCS to incorporate fresh produce into meals purchased from small farms in New York.

The "Stickball Bill" was his personal favorite, Gibbs told me.

After the bills passed, he said, a couple of East Harlem sports groups thanked him by giving him a signed stickball bat, which proudly hangs on his office wall with a hockey stick and a baseball bat—also ceremonial gifts from constituents.

Gibbs called it "one of the most powerful moments in my election career—organizations thanked me for a bill that I passed to help them advance stickball in the Puerto Rican community."

I asked Gibbs what was next for him. He cast his resignation as an opportunity to fight harder.

"It gives me an opportunity not be handcuffed anymore," he said. "In fact, I will be taking a more aggressive stance as it relates to prison reform, criminal justice reform."

He said he gets out of bed everyday and comes to the State Capital "because there's a need. People need help. Whether in prison, or out of prison."

"The world needs 'People-Ticians," Gibbs concluded. "And I'm the People-Tician."

One of the people Gibbs regularly speaks with that most people prefer to avoid. Photo credit: JB Nicholas.

Before I left Gibbs to it, there was one last thing I needed.

I wanted a photograph of him staring into the Assembly Chamber—the place he hasn't been back inside since his run-in with Assemblymember Brown last year.

Gibbs stepped up to the glass doors of the Chamber and stared longingly inside. I quickly photographed him and we started to leave. I would head to my car for a long drive to my Adirondack mountain home. He would first go back to his office, then a hotel.

But, again, Gibbs stopped to talk to someone everyone else ignored.

The woman had a deformed face and a half-dozen or so poster-sized anti-abortion signs arrayed around her at the entrance to the chamber. For a protester, she occupied a strategic chokepoint. Since the public is not allowed inside the chamber, this was the closest she could get to lawmakers to make her voice heard.

Gibbs and the woman, Shelia Blasch, were so familiar with each other they hugged before chatting for a few minutes. I stood there and watched everyone else try to ignore her—and her anti-abortion signs. To New York's mostly Liberal lawmakers, she was nuts. To her, they were murderers.

Here was the best of Edward Gibbs. The Gibbs the retired parole officer, Lesser, said "had a black belt in gently dealing with people that were 'affected'" with the same "grace" his social worker mother showed people for 44 years. When he finally said goodbye to Blasch, I walked with him a little ways down the hallway before saying goodbye. Then I circled back to Blasch.

The 68-year-old called herself a pro-life advocate. She said she'd been regularly protesting against abortion at the Capital since 2019, when the legislature passed what it called the "Reproductive Health Act." Blasch called it the "Reprehensible Homicide Act." She said she'd been chatting with Gibbs for the "last couple of years."

"I think he's a nice guy," she said. "He's always very respectful."

Gesturing to the Assembly Chamber, she added "I'm glad to see he's fed-up with some of the things they're doing."

Send tips or corrections to jasonbnicholas@gmail.com or, if you prefer, thefreelancenews@proton.me